Photo by Spencer Tweedy (Flickr Creative Commons)

Ontario’s back-to-school season is going to be especially disruptive for families later this year. Those of us with an interest in the state of our schools, and the well-being of children and the people who help support them, need to get ready—and get to work.

Doug Ford’s government has given us some sense of what to expect, though the plans are strategically vague. For example, teachers have been threatened with discipline if they stray too far from the 1998 sex-ed curriculum, but a provincial lawyer has suggested the lauded 2015 revision was fine as a “supplemental” resource. The message: teach the new stuff, if you dare.

Other Conservative changes have been easier to tabulate. Cancelling the province’s cap-and-trade program created a $100-million hole in the budget for fixing school infrastructure. Further “strategic” cuts have been made to funding for rewriting the curriculum to accommodate Indigenous education, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and American sign language, as well as for additional math training for teachers. Parents Reaching Out grants, which helped school boards engage more effectively with parents from marginalized communities, were also cut.

Collectively, these decisions represent fairly small sums of money. But they will have a disproportionate impact on how classroom content and the institutional structures of education can respond to and reflect the educational, societal and socioeconomic needs of kids, families and communities.

More recently, Education Minister Lisa Thompson has floated the idea of “revisiting” the class-size cap for kindergarten and grades 1–3 as part of the government’s goal to cut 4% from the cost of public education. Thompson has refused to commit to full-day kindergarten past the next school year, out of respect for the “consultation process,” though she adds, again quite vaguely, the government will be maintaining “full day learning.”

Thompson’s government is also talking about revisiting the process by which school boards deal with staffing and seniority for occasional teachers. Rather than directly funding services for children with autism—let alone increasing the inadequate funding currently provided—the government will simply give money to parents in what resembles a “vouchers by stealth” initiative.

And last fall, after a meeting of provincial education ministers, Alberta’s David Eggen claimed he heard his Nova Scotia counterpart, Zach Churchill, “bragging” about “how he was taking it to school boards and dissolving them and centralizing the power.” Nova Scotia is not alone in this regard. Quebec has committed to abolishing school boards and replacing them with service centres (the Nova Scotia model in the English system). Manitoba is also looking at reducing or eliminating boards in the province.

Placing limits on local democracy isn’t new to Doug Ford. Fresh into his current mandate, the premier promised he would use the Charter’s notwithstanding clause if needed, in the middle of a municipal election campaign, to forcibly reduce the number of wards in Toronto from 47 to 25—a decision that impacted both the public and Catholic Toronto school boards even if it didn’t reduce the number of trustees in either system.

***

What’s been laid out for public education in Ontario is a roadmap to social and economic regression. The best, and I would argue only option—if our goal is not just to brace for impact, but to demand long-term improvements to the provincial education system—is massive and sustained mobilization. That’s going to take a lot of work, outreach, listening, and the ability to suspend our understandable defensiveness after being under attack for so long.

Teachers and education workers are a perennial and predictable target of those in positions of power—in Ontario, B.C., Quebec, Nova Scotia and everywhere in between. Education workers are invariably right there on the frontlines, or rather their unions are, defending their collective rights and the quality of our provincial school systems.

In Ontario, that fight will be waged fiercely at the bargaining table in the lead-up to the expiration of collective agreements on August 31. But in addition to this work, alliances need to be forged with other groups whose support undercuts the government’s narrative instead of reinforcing it. These alliances must be ready, well in advance, for picket lines, work to rule, preemptive back-to-work legislation and whatever else the government might throw at our teachers after the start of bargaining.

By “other groups" I mean high school and middle school students, who showed their impressive mobilization skills in cross-province rallies protesting the rollback of the sex-ed curriculum. But I’m also talking about parents, even grandparents, given that these are the people the Ford government keeps saying it’s out to protect and support.

Within these two groups, though, we need more than just the usual public education advocates coming out. Single parents and parents who work shifts. Parents of colour and Indigenous parents. LGBTQ2 parents and ESL parents. If we don’t know how to listen to each other and work together, particularly with those who have been traditionally marginalized or left out of the debate—by design or by neglect—people run the risk of feeling increasingly isolated. Our numbers suffer, and the powerful win.

Recent events show us that isolation can make people particularly susceptible to arguments that bureaucracies can’t be trusted; that schools don’t listen to parents, taxes are too high and money is wasted. The powers that be want people to feel they can go it alone because, they claim, public sector workers including educators have their own agenda and it has something to do with more money and more benefits.

This is the narrative we need to push back against if we’re to reverse the damage being done every day. That task is all the more difficult with the Ford government tapping into real populist disillusionment and anger at the nameless, faceless elites allegedly ruining this province.

The good news is that when it comes to cutting through the isolation and the disillusionment, educators and education workers have a huge advantage over a lot of other workers in a lot of other sectors.

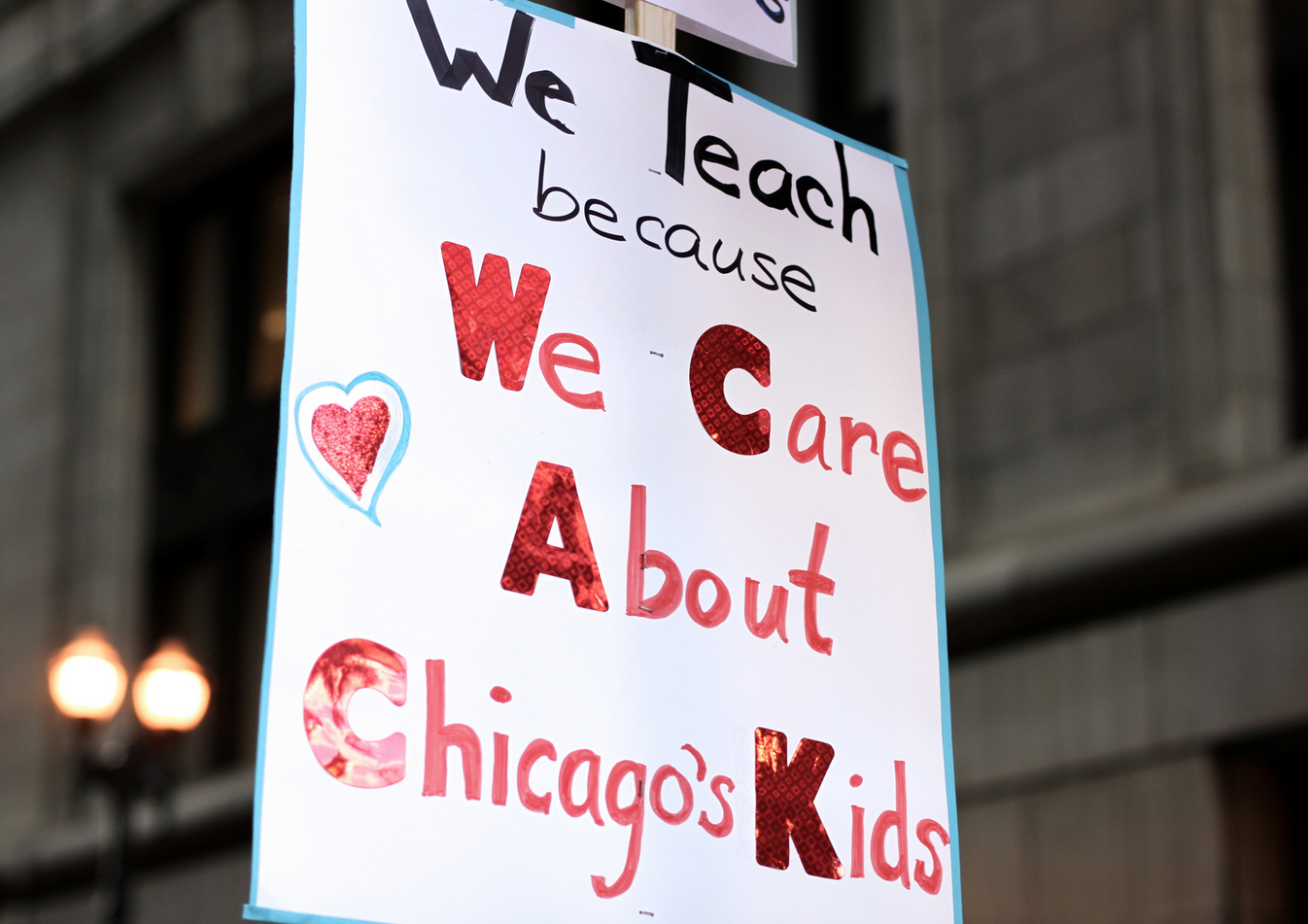

Parents and education workers have one very important thing in common: the desire to help care for and support kids. It’s a powerful shared goal that’s hard to argue against. It provides a ready-made starting point to connect to a wider circle of advocates for our kids, our communities, our schools, our most vulnerable, and a system that provides equitably for all of us.

To directly confront the all too effective divide-and-conquer strategy governments roll out to fight teachers, we need to build a movement that emphasizes what we can all do to help each other out. Where the government focuses on wages and benefits to reinforce the narrative of entitled union members, educators need to talk to and with parents, children and the public about what would be best for the kids, their families and the community.

In 2012, members of the Chicago Teachers Union used their visibility and privilege where they worked and lived to support those who needed their help in making their communities better for themselves and their families. And those communities supported them in return. That’s the solidarity we need to create the conditions for sustained momentum.

***

In Ontario in the lead up to August 31, self-declared progressives need to reach out to and enlist an increasingly fractured populace in ways we haven’t had to do in decades. This involves the tried and tested method of talking to people—communicating with each other face to face rather than, or as well as, through the screen of a computer or mobile.

Organizing ourselves will also require physical spaces for people to gather. While austerity has severely undermined much of the remaining community-based infrastructure from which to (as my dad would say) plan the revolution, we do have schools. And this is where this fall’s teacher bargaining bonanza could have benefits far beyond the securing of another collective agreement.

Organizing around schools can help us build communities that are immunized from political campaigns that keep us divided by amplifying our anxieties and emphasizing what separates us from each other (without, of course, identifying the systemic forces behind these divisions). Local organizing puts kids and communities at the heart of the conversation, but this can and should also be a segue to discussions about taxation, inequality, spending, justice, racism, colonialism, health and well-being, food security, housing, etc. All topics that some people don’t feel equipped to jump right into, but who might be able to find their way into through discussions about the local school.

Most parents, students and pretty much anyone you run into on the street will tell you it makes obvious sense to cap class sizes, so that kids get the best education they can. As the Ford government threatens to lift those caps yet again, we all need to remember that they were not put in place out of kindness. Classroom caps were won by educators and their unions through the collective bargaining process. They fought for the caps not because it made their lives easier, but because teaching conditions affect learning conditions.

When collective agreements expire on August 31, and educators are in a strike position, or are rejecting concessions demanded by the province, or are being threatened with (possibly pre-emptive) back-to-work legislation, remember what’s at stake where our kids’ education is concerned, and what education unions have been fighting for.

And be prepared to fight—not just for them, but for the gains they’ve made on our behalf, and the gains we need to continue to collectively make for the next generation.

Erika Shaker is a senior researcher at the CCPA and director of the centre's education project.