Illustration by Eagleclaw Bunnie

Connect. Search. View. Share. Like. They are the calls to action of the digital revolution, the latest stage, we are told, of a radical change in how society works, plays and interacts. Since the late 1960s, and in conjunction with Silicon Valley’s development of “disruptive” tech, American CEOs and scholars have emphasized what’s new and different in the present as compared to the past. Peter Drucker (The Age of Discontinuity: Guidelines to Our Changing Society), Daniel Bell (The Coming of the Post-Industrial Society), Alvin Toffler (The Third Wave), Nicholas Negroponte (Being Digital), Esther Dyson (Release 2.0: A Design for Living in the Digital Age) and Google’s Eric Schmidt and Jared Cohen (The New Digital Age: Reshaping the Future of People, Nations and Businesses) all proposed that digital technology was moving society toward a much different and better future.

Quantitatively, the current scale of digital activity suggests an important social transformation. In the first month of 2019, Facebook had 2.32 billion monthly users—a sum more than double the total combined populations of the 29 countries that make up the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Every minute of the day in a month, four million videos are watched on YouTube and over 400,000 tweets are sent on Twitter. 40,000 Google searches happen every second. All of this digital interaction adds to the 2.5 quintillion bytes of data that gets produced each day.

But numbers can be deceiving. In this case, more important than the measurable quantitative impact of the “digital age” is who benefits from this so-called technological revolution, who is left out, and how the technology alters (or not) social relations and power structures.

During the 1984 TV broadcast of the Super Bowl, Apple Inc. famously launched the ad “1984.” A play on George Orwell’s dystopian science fiction novel, “1984” associated Apple’s business with freedom from government control and introduced the company’s new Macintosh computer with a statement of revolution. Soon after, hundreds of thousands of Americans marched to the mall and spent $155 million on Apple products, a boon to Apple’s total accumulation of $1 billion in revenue that year.

Four years after “1984” helped Apple brand its computers as a tool of countercultural revolt, the American president Ronald Reagan visited Moscow State University and lectured students about the digital revolution. Standing beneath a bust of Lenin, Reagan declared that a “technological revolution” was “quietly sweeping the globe, without bloodshed or conflict.” In an attempt to persuade Soviet youth to reject their state’s Marxist-Leninist icons and accept the U.S.’s neoliberal path to a post-socialist future, Reagan depicted the “vanguard” of this global revolution as “the entrepreneurs,” the “men with the courage to take risks and faith enough to brave the unknown.”

For Reagan, history’s primary actors were not workers but the late Steve Jobs and his Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak, who started “one of the largest personal computer firms” from “the garage behind their home.” Today, brand strategists for corporations represent everything from Gillette razors to cordless Apple earbuds, virtual reality, the “internet of things” and artificial intelligence as radical technologies that will change everything. Politicians advance rosy ideas about how digital technology will disrupt the old and let us begin anew.

Such ideas are now firmly embedded in mainstream media discourse and shape the public mind. Do a Google search for “digital revolution” and in less than a quarter of a second you will be presented with millions of headlines declaring it “is here.” Captivating and exuberant as that idea may be, it does not offer the public a clear view of what’s actually going on, nor does it provide public policy-makers with useful knowledge of what’s really driving change.

For starters, a significant prerequisite to being included in the digital age is access to digital technology. Yet access to the internet, computer hardware and software, and the digital literacy skills to effectively use them, is nowhere close to being universally provisioned. At present, only about half of the world’s population is online. Less than half of the world’s households own a personal computer. Fewer own a smartphone. The divide between the digital haves and have-nots is vast between and within countries.

While the United Nations’ Human Rights Council resolved in 2016 to support the “promotion, protection, and enjoyment of human rights on the internet,” only a few countries treat internet access as a citizenship right; most relegate it to a consumer choice. Each year, big telecommunication companies (e.g., AT&T, Verizon Communications, Rogers, Bell) make billions selling internet access as a commodity to those who can afford it while excluding those who cannot. The diffusion, use and impact of digital technology, far from encompassing humanity as a whole, is unevenly developed and unequally accessible. Not everyone lives in and benefits from the digital age.

More fundamentally, the notion that this new age is revolutionary is outright misleading. A revolution implies a sweeping transformation of society as a whole, something that breaks with what came before. Whether fast or slow, violent or peaceful, revolutions happen when a people finds the will to overturn the inequitable conditions of an older social order, thereby bringing about the possibility of building a different type of society. The popular will may be mobilized with help from new technologies (or revolt against them), but they are never the cause of revolution.

Those who say otherwise subscribe to a type of technological determinism, a reductionist theory of social change that takes technology to be the central agent in society and the cause effecting society’s greatest transformations. During the Obama presidency, for example, the U.S. State Department, CNN and FOX News represented American social media platforms as drivers of popular revolts in states that U.S. hawks wanted to topple: Iran’s 2009 “Twitter Revolution” and Syria’s 2011 “YouTube Revolution,” for example. It was a one-dimensional explanation of the more complex economic, social and political conditions that produced these mass uprisings.

Societies are always changing. Undoubtedly, some or many of these changes—in the world’s conflict zones and here in relatively stable Canada—are related to digital technology. Yet there are important continuities with the past that tend to be overlooked by those who say we are in an altogether new age.

Around the world, corporations continue to accumulate profit amidst widespread poverty; national security, not welfare enhancement, continues to preoccupy state governments. These two most important institutions of modernity—capital and the state—will deploy today’s digital tools, as they have past technological advances, to reinforce their power, reinvent their control and recompose their action.

It is in this sense, taking into account the many people who are not living digitally, that we should see the new technologies not as inherently revolutionary, but as part of a reformation of society’s same old power structures.

Digital Technology Inc.

To really understand digital technology, we need to render it intelligible in human and social terms. This requires us to free ourselves of the jargon of technological determinism that obscures a clearer view of how digital technology is produced within a capitalist society. Only then will we be able to observe how society’s pre-existing political and economic structures constrain and enable, influence and are influenced by, digital technology.

No technology invents itself. All digital developments—from smartphones to search algorithms—get made in society, and most of the time by some people at the behest of other people working in government (e.g., the U.S. Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency), the corporate sector (venture capitalist–funded tech firms), and universities (tech incubators at MIT and Stanford University). We could hold these organizations uniquely responsible for the social consequences (good or bad) of their disruptive innovations, but that would assume that they, and the digital technology they create, exist in a social vacuum, which obviously they do not.

The organizations that make digital technology are themselves shaped by even larger societal structures—the most significant being capitalism, a dynamic system characterized by private ownership of the means of production, class division, waged labour, production oriented to profit (not human need), and inequality, class conflict and international, frequently imperialist expansion. Far from being disrupted by digital technology, capitalism has been given a firmware update; the system’s underlying code continues to direct new technologies toward profit-maximizing ends.

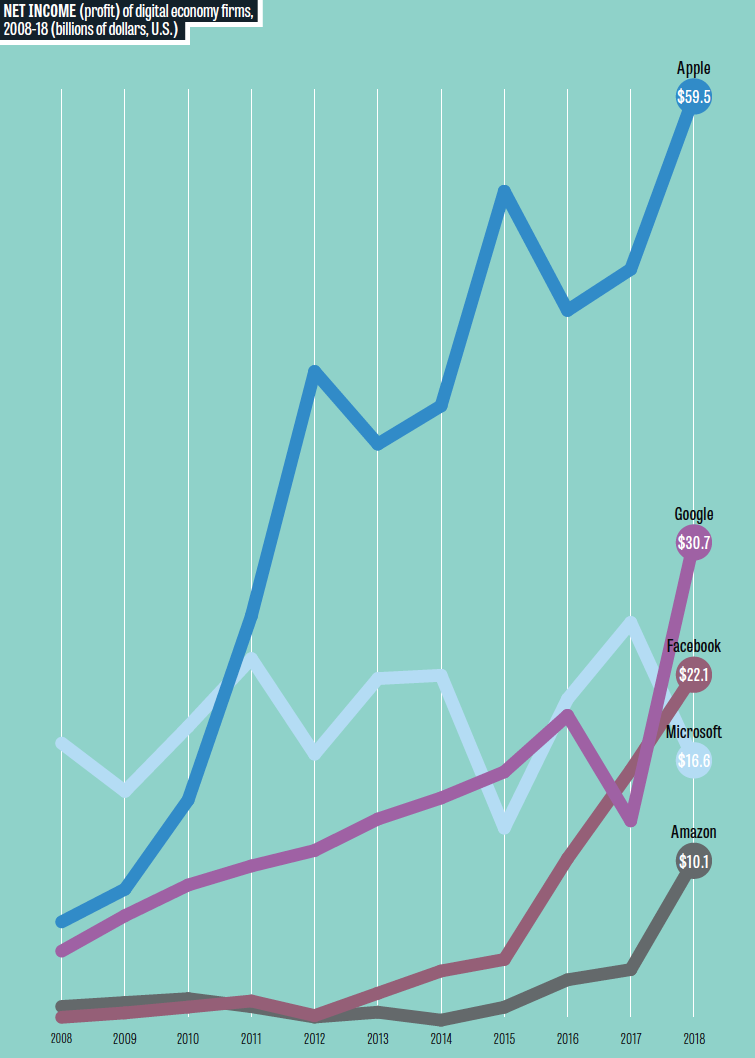

In the digital age, the owners of the means to produce, circulate and reproduce digital technology are corporations (beholden to private shareholders), not governments (beholden to the public). Currently, the U.S. is headquarters to the majority of the world’s largest computer hardware, software, service, storage device and semiconductor corporations, as well as the biggest internet and social media businesses. According to Forbes’ Global 2000 List of the World’s Largest Public Companies, the five most valuable corporations in the world by market capitalization are digital titans: Apple ($926.9 billion), Alphabet-Google ($766.4 billion), Amazon ($777.8 billion), Microsoft ($750.6 billion) and Facebook ($541.5 billion).

In 2018, Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google—the “FAANG” in investorspeak—accounted for more than 11% of the S&P 500 index and an even bigger share of Wall Street’s decade-long bull run. At the end of 2018, Apple and Amazon had become the first corporations in the world to be worth over a trillion dollars. Private corporations like these, not the public, own the labs where digital hardware and software is researched and developed (R&D), the networks of factories and offices where digital goods and services are assembled, the retail nodes where these goods are circulated, and the databases where digital information about users is stored. Capital, not the commons, controls the patents to digital innovations, as well as the copyrights to digital designs.

The divide between owners and workers also persists in the digital age. Again, the FAANG are institutionalized expressions of the broader social schism. Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos is worth about $131 billion (slightly less after his divorce from the author MacKenzie Bezos), making him the world’s richest person. Bill Gates continues to be a shareholder of Microsoft, his $96.5 billion net worth putting him up there too. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg is worth over $62.3 billion. Subordinate to these doyens of the digital are workers—the people who sell their labour power on the job market in exchange for the wages they depend on for their lives.

The stars of Silicon Valley are like any other corporation in that they buy the skill and time of workers to do tasks within a complex division of labour. They direct the hands and minds of these workers to befit their goals. From doing R&D for hardware and software at the Apple Park in California to living the brand at Apple retail stores around the world, 132,000 waged workers toil for Apple Inc. To make its search engine run each day, Google relies upon 99,000 AI researchers, Google Ads sales agents and big data and analytics cloud consultants.

Amazon exploits the labour of about 600,000 workers at massive fulfilment centres: “packers” sort commodities into boxes round the clock; logistics and shipping workers rush to deliver orders to customers, sometimes within hours of their online purchases. While Facebook and YouTube profit from the “free labour” of their users—who generate the content that keeps people coming back for more—they also pay wages to about 40,000 workers: software engineers, data site managers, and content moderators who delete the posts that violate their community guidelines.

Moreover, digital technology companies produce and sell goods and services as commodities for exchange in the market, not as a way to meet human needs. Though they package their operations with uplifting slogans, tech corporations are structured and restructured to maximize profits. Just like any other company they are obligated to ensure their shareholders get a return.

In 2018, Apple took in $53.53 billion in profit by motivating its billions of consumers to “Think Different” while all doing the same thing: buying lots of Mac computers, iPhones and ancillary products. In its 2017 “Building Global Community” manifesto, Facebook declared that it was developing a “social infrastructure for community.” Yet Facebook’s data-veillance platform exists to aggregate personal information about individuals, commodify it, and sell advertisers access to user attention.

Each day, thousands of advertisers competitively “bid” to buy what Facebook sells: the opportunity to expose the social network’s users to targeted and algorithmically placed ads for their commodities direct to personal feeds, Messenger, Audience Network and other mobile apps. In 2018, Facebook accumulated $17.8 billion and its average user profile was worth approximately $25.

In 2015, Google became a subsidiary of Alphabet, swapping its “Don’t be evil” motto for “Do the Right Thing.” In 2018, the right thing included seizing upon the data generated by one billion people conducting over 3.5 billion Google searches per day in order to generate $115 billion in ad revenue. Amazon exerts oligopolistic control over the global e-commerce market, but much of its US$10 billion in profit last year came from the sale of web services to clients and user attention to advertisers.

Whether producing and selling technological hardware and software, running commodity logistic chains, or abiding by a “freemium” business model conceptualized variously as “platform capitalism,” “data capitalism” and, more recently, “surveillance capitalism,” the day-to-day conduct of corporations in the digital age is motivated by profit, not social uplift. And far from heralding a more equal society, the digital age is typified by growing class inequality and oppression.

In 2018, as corporate productivity and profits soared, the gap between the rich and the poor widened. The globe’s 26 richest people owned as much wealth as the poorest 50%, and the wealthiest 1% of the global population owned more than half of the world’s total wealth. The average CEO-to-worker pay ratio was at least 339 to 1, and as CEO compensation increased, wages stagnated.

The Chinese workers assembling iPhones at Foxconn’s industrial complex earn about $5,000 a year, roughly 4,200 times less than the average Apple CEO. It takes Jeff Bezos 11.5 seconds to earn the annual salary (about $30,000) of his workforce. While tech jobs are often glamourized as high-paying, nine in 10 Silicon Valley workers scrape by on subsistence wages, making less in 2018 than they did in 1997.

As social inequality increases in the digital age, so do expressions of class conflict in the sectors associated with technological progress. Historically, tech and other “digital age” workers have been difficult to organize. Recently, though, there are signs of change and rising class consciousness. Some workers are collectively resisting the degradation of increasingly part-time, poorly paid and precarious forms of employment, racial and sexual discrimination on the job, and the general dispossession of their knowledge. They are joining or forming unions, holding one-day strikes or even quitting, or simply slacking to protest managerial control.

Over the past few years, Amazon workers have launched unionization campaigns. Across digital newsrooms from Jacobin to VICE, journalists have formed unions to demand better pay, job security and benefits, as well as equity policies and editorial freedom. Google workers have come together to demand that the company cut its ties to the military-industrial-complex. Facebook users have built unions to demand more control over, and compensation for, the data they produce for the company.

Nonetheless, U.S. based digital corporations continue to expand around the world. Though China-based giants Tencent, Alibaba, Baidu, Qq, Toaboa, Tmall and JD are also “going global,” the reality is that U.S. firms own the lion’s share of digital age hardware and software, intellectual property rights, platforms, sites and services, and user data. The U.S. state supports the global ambitions of Big Tech through foreign and trade policy, and by using its geopolitical and economic heft to knock down national regulations that prohibit or limit the ambitions of America’s digital economy players.

To be fair, most countries don’t need much convincing. Under the sway of neoliberal ideology, foreign governments see acquiescence to U.S. digital policy norms as synonymous with “development” or simply as a source of investment in the so-called jobs of the future. They offer the FAANG, “on demand” services firms such as Uber, and other tech giants subsidies, tax breaks and promises of minimal to zero regulatory oversight.

In more aggressive cases, states are adjusting government programs and agency priorities, building entire communities and moving populations to meet the human capital demands of U.S. digital titans. The costs of supporting digital accumulation are thereby socialized while the returns on digital development by and large flow back and are absorbed by U.S. capital.

Revolutionary potential

So far, the economic and political structures that sustain the unequal division of work and highly inequitable distribution of wealth under capitalism are rejigged but not radically altered in the “digital age.” Significant increases in society’s digital interactions and reliance on computers have not (yet) qualitatively changed how we organize ourselves and are governed by the state. These interactions, notably the proliferating intrusion on privacy by digital corporations, are no doubt highly disruptive of individual lives, yet the capitalist system that profits on this disruption is unchanged.

Does it have to be this way? In the 2015 book PostCapitalism: A Guide to Our Future, the British journalist Paul Mason argues that digital technology possesses the imminent potential to break out of the reigning system. According to Mason, digital technology and networked individuals are, borrowing Marx’s and Engels’s term, capitalism’s new “grave-diggers.” He predicts capitalism will come to an end, not by revitalizing a democratic socialist movement and empowering the working class to change the system, but by emancipating digital technology from the chains of the states and corporations that keep them private and scarce.

But like the generations of techno-utopians that preceded him, Mason puts too much faith in the power of digital technology to automatically move society to a postcapitalist future. The long history of capitalism provides no evidence in support of this claim. Social reforms and revolutions do not happen because technology is left to its own devices.

Undoubtedly, some digital experiments can chart alternate routes to future sociality. The political left in Canada might begin to challenge the private interests of the FAANG by taking a multi-faceted approach to public policy-making that aligns with the principles and values of social justice. Antitrust laws could be used to diminish the growing monopoly powers of the digital giants, for example. Given that public subvention gave us the internet, which capital later seized, privatized and charged us to access, perhaps it should be returned to us as a public utility.

At home and internationally, we should fight to make internet access universally accessible—a basic social right. Moreover, we can loosen the FAANG’s grip on our data by supporting augmented privacy rights and boycotting surveillance capitalists. Instead of messaging with Facebook’s WhatsApp, use Telegram. Stop using Google and start using DuckDuckGo. Furthermore, we need to push FAANG to pay more taxes and be less of a drain on public wealth. Billions in public subsidies help the FAANG grow and prosper, yet these companies are chronic tax evaders and avoiders. In addition to ensuring they pay their share, the billions that Facebook and Google annually accumulate in online advertising revenue could be taxed, with a portion of those monies put toward a public fund for diverse, independent and public interest journalism.

Reforming digital capitalism cannot happen without an educated citizenry that is willing and motivated to participate in democracy. The FAANG know everything about us, but we know so little about them. We need to pry open their black box, shine a light on its circuitry, and make its workings transparent and knowable to all. The more we know about how the system has been made to work, the easier it will be for us to tinker with or radically redesign it.

At all levels of the public education system, digital literacy must be a priority, and one that does much more than equip workers with the technical skills that digital capital demands of them. Educators should strive to empower citizens to understand how society shapes and is reshaped by digital technology. We can inspire citizens to make reasoned judgements about digital technology and debate its costs and benefits with regard to the norms and values of social justice. Outside of academia, we should build inclusive and democratic community spaces where educators, organizers and workers collectively learn about digital capitalism and imagine strategies and tactics for pushing beyond it.

This is not the future favoured by most of the big organizations at the helm of the digital age. Nor is postcapitalism a strategic priority for the CEOs, neoliberal politicians and professional technocrats that make major decisions in the digital age. A postcapitalist future is not an investment priority for the finance capitalists putting their money into the future-leaning digital corporations that build market-facing digital technology to make working, shipping, shopping and speculating more lucrative for other corporations.

Digital technology does not itself change the world, but we can use and redesign it to fight for a sustainable and different future in which all are freed from the realm of necessity, and where all are empowered to participate in democracy. If we want techno-postcapitalism on the agenda, in other words, we will need to put it there ourselves.

Tanner Mirrlees is an associate professor of communications and digital media studies at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology (UOIT) and Vice-President of the Canadian Communication Association. He is the author of Global Entertainment Media: Between Cultural Imperialism and Cultural Globalization (Routledge, 2013) and Hearts and Mines: The US Empire’s Culture Industry (University of British Columbia Press,2016). He is also the co-editor of The Television Reader (Oxford University Press, 2012) and Media Imperialism: Continuity and Change (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).