Original graph by Jordan Brennan for Maclean's magazine.

I grew up on constant strike. And I am not saying this metaphorically. During my childhood in Argentina, public sector workers, including both my parents, were literally on strike for days, and sometimes weeks, every single year. Teachers went on strike every March (the beginning of the school year) and usually one more time before the year was out, as new austerity measures were announced by the provincial or national governments of the time.

Budget deficits, the need to cut “red tape,” and a permanent state of austerity were the rule in Argentina during the 1990s. We were the poster child of neoliberalism. But then we became a poster child of resistance, with a social explosion that included blockades in major cities, general strikes and factory occupations. (Canadians might remember some of this in Avi Lewis’s documentary with Naomi Klein, The Take.)

Even as a kid I was somewhat aware that the majority of these strike actions would be defeated. But sometimes you win. And that feeling of power, of victory, of knowing you finally broke the back of the bosses and they have to give in…. That feeling feels pretty good.

Fast-forward to December 2016. I found myself sleeping inside the building that houses Argentina’s Ministry of Technology. The strike and occupation went on for a week, to fight back against layoffs and a reduction in the budget dedicated to research. I was a researcher at the time and an active member of the public sector union. Researchers and scientists did not historically identify as “workers”; they belonged to a different category called “scientists.” To make any kind of strike happen, we would need to make sure our colleagues identified as both.

We spent the entire year leading up to that December organizing workplace after workplace. The budgetary adjustment was so brutal that even the most renowned “scientists” came out in support of the strike. I had never before participated in a 1,000-person assembly to decide a strike vote. That was remarkable.

The strike and the occupation were not legal, but they were massive and successful and the government caved in. Adjustments for that year were cancelled, so were the layoffs. Did we get everything we wanted? No. Did it feel for a moment like we could topple a government? Yes.

The right to strike in Canada

Since moving to Canada almost two years ago, I have noticed similarities between the current advance of the right against unions and what I witnessed in Argentina during the 1990s. I was surprised that aggressive government policies against unions did not trigger general or large strikes, until I learned that legal restriction on “political strikes” has become an ingrained feature of labour disputes in Canada.

I also learned about the Rand formula and the system it created of strong collective bargaining, allowing for improvements in wages and working conditions; a system that has also maintained an overall high union density, especially in the public sector. A similar system of labour relations in Argentina led to over 60% unionization toward the end of the 1980s.

However, as was the case in Argentina during the harshest neoliberal period, right-wing governments do not care for the limits imposed by legislation when attacking unions. In the last few years in Canada we have seen the right to strike under attack, affecting especially public sector unions, reinforcing restrictions that already exist for labour action in the private sector.

Governments of different political stripes have clearly stated that the right to strike in Canada is limited to strikes that do not seriously affect the functioning of society and the economy. Every time a strike starts to noticeably disrupt people’s lives—the lives of business owners perhaps most importantly—back-to-work legislation is brought in, only to be challenged in the courts years later. Canada has witnessed hundreds of small strikes in the private sector that do not necessarily affect the overall economy. But the moment a strike, even a legal strike, threatens economic or political interests, back-to-work is the answer.

We witnessed it in Ontario with the college faculty strike, in which thousands of precarious workers around the province were forced back to work by the previous Wynne government. Similarly, the still new Ford government legislated York University workers back to work as one of its first actions after being sworn in. The federal government under Prime Minister Trudeau sent postal workers back to work once the strike seemed to be heading in the direction of a total stoppage around Christmas.

Arguably the most problematic recent example of back-to-workism was against the power workers in Ontario at the end of 2018. With a negotiating deadline approaching and no solution in sight, the Ford Conservatives, with support from the lone Green MPP and the Ontario Liberals, voted pre-emptively to forbid any strike in the power sector.

What incentive does a company have to negotiate in good faith with its workers, to bring positions closer, if it knows that at the end of the day, back-to-work legislation will tilt the scales in its favour?

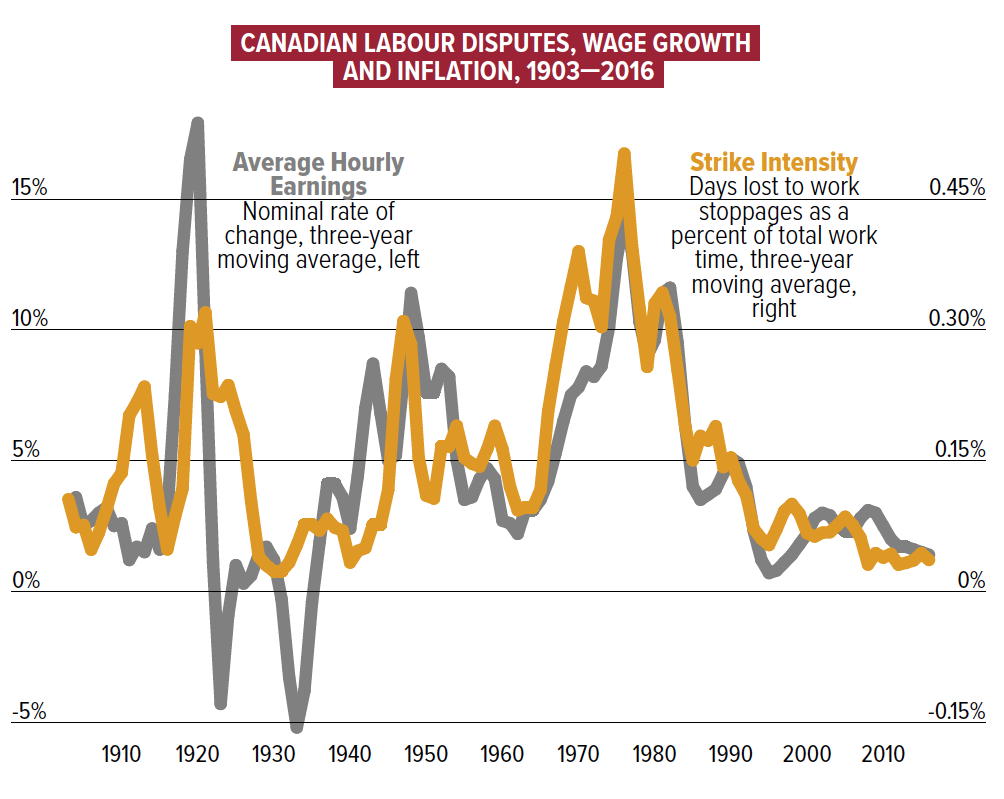

These attacks on unions, and especially on union strongholds like the public sector, have hampered the capacity to take strike action, which is already comparatively weaker in the private sector. Despite some high-visibility strikes in the last two decades, the total number of hours lost due to work stoppages has declined significantly since the 1970s (see the chart here from Jordan Brennan, part of Maclean’s “91 most important charts to watch in 2018”), to the point Canadians now strike about as much as they did during the Great Depression.

Defending collective bargaining by striking

Collective bargaining is under attack and employers are increasingly hostile to the notion of negotiations. Gains for unionized workers are still made in collective bargaining agreements, but decreasing union membership, especially in the private sector, implies that those gains represent a smaller portion of the working class. In the context of “competitive pressures,” why would an employer negotiate better conditions? They wouldn’t—unless there were the chance of workers withholding their labour power, the source of all company profits. A company can declare a lockout or shutdown, avoiding negotiations altogether. So should workers consider this as one of their options.

The Rand formula system has produced significant improvements to workers’ lives, allowing unions to grow and take care of their members. But it assumes collective bargaining takes places within a political context in which labour rights are respected. That is not the context at the moment, and the challenges to the system itself require a more direct confrontation with employers. The system can only be strengthened in labour’s favour by direct action.

The recent teachers’ strikes in the U.S. demonstrate the need to return to a strike cycle that actually disrupts a sector, or even an entire society. Teachers in West Virginia were not allowed to strike, but they went ahead anyway with a massive rank-and-file strike that was formally deemed illegal. It nevertheless gathered enough momentum to force the political class to sit down and negotiate.

The government shutdown used by U.S. President Donald Trump to push his administration’s conservative agenda extended for more than 30 days and was only cancelled when air traffic controllers threatened to strike due to unsafe working and flying conditions. That strike would have been considered illegal, too.

The recent Canadian postal workers’ strike was a threat because of the massive disruptions it would have created so close to the holidays. An Ontario power workers’ strike carried the same potential. A sustained challenge to the restrictions on strike action, going beyond the courts, may be a necessary step to actually defeat anti-union/right-to-work schemes.

A road ahead

If there is anything to learn from workers’ experience in Argentina, it’s that if you don’t get directly in the way of anti-worker plans, you will have little to no chance of stopping them.

Premier Ford and the Progressive Conservative government in Ontario typify this attitude: going after student unions (even accusing them, in another throwback to the Winnipeg General Strike, of “crazy Marxist nonsense”), scrapping labour rights, freezing the minimum wage and floating the privatization of key public services like transport and health care. Unions and social movements have many fights ahead.

Strikes build power even if they settle for less than expected. The workers who filled the streets of Winnipeg 100 years ago recognized this core truth. That work stoppage did not take place in a vacuum, but rather at a time of high labour militancy throughout different industries.

Corporations hold about as much relative wealth and political power today as they did in the early 20th century. If workers had to strike then to correct the imbalance, it’s hard to see how we will level the playing field again now without doing the same—and on as large a scale. What better way to honour their actions than to emulate them?

Bruno Dubrosin is a labour organizer based in Toronto. He is the co-ordinator of the One Million Climate Jobs campaign at the Green Economy Network.