Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has his hands full when it comes to free trade. As his government scrambles to understand the implications of the Trans-Pacific Partnership Trade Agreement (TPP), another deal, the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) with the European Union, raises many of the same, and some uniquely troubling, issues.

Both CETA and the TPP include a highly problematic investor–state dispute settlement process, for example, which will multiply the number of corporate lawsuits challenging public policy that Canada already faces under NAFTA. But only one of these new deals (CETA) encroaches worryingly on the ability of provinces, municipalities and other public institutions to favour domestic food and support national farmers in public procurement contracts.

Given widespread food insecurity in Canada, and the absence of a national food policy, municipal and provincial initiatives are essential for ensuring sustainable, local agricultural production. Public procurement of local food—food grown and consumed within a province, territory or other specified geographic area—is recognized as a key pillar of food security because it addresses both supply- and demand-side issues.

On the supply side, procurement offers market access for small-scale producers and cushions them from market shocks. On the demand side, the availability of local food not only increases consumer choice, but generates local economic activity as well. There are also well-recognized environmental, social and health benefits associated with the production and consumption of fresh, in-season local food.

Support for local food in Canada has never been stronger, with provinces such as Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia and Nova Scotia leading the policy charge. The government of Ontario’s Local Food Fund (LFF) has provided $22 million to support 163 local food projects, for example. To date, the fund has leveraged $102 million in investment to expand local food markets.

Cities and municipalities are also pioneering strategies to support the public procurement of local food. The City of Vancouver has a food strategy that promotes localprocurement as a key driver of its sustainable food system. In 2011, the City of Toronto passed a local food procurement policy that inserts language into requests for proposals designed to increase the amount of food grown locally.

Elsewhere in Ontario, the cities of Thunder Bay and Markham allocate 10% and 25% of their respective food budgets to locally grown food. Dozens of other cities in Ontario have projects to support local food, largely with the support of the LFF. Local food procurement is endorsed by the 60+ Food Policy Councils across Canada, as well as by an extensive network of non-government and business partners.

In addition to municipalities, academic institutions, school boards and hospitals (collectively referred to as the MASH sector) provide a significant market for local food producers. The broader public sector spends around $745 million on food annually in Ontario. MASH institutions are increasingly developing new strategies to boost local food content in their procurement contracts. There are dozens of examples but leaders in Ontario include the University of Toronto, University of Guelph, and health care facilities including St. Mary’s Hospital in Kitchener and St. Joseph’s Health System.

The Canada–EU CETA could undermine such initiatives through its new restrictions on public procurement at the provincial, municipal and MASH sector levels—all previously excluded from international free trade and procurement agreements. The restrictions in CETA prohibit covered institutions from giving purchasing preference to goods or services from local companies or individuals if the contract exceeds 200,000 Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), which is about $315,500 in approximate 2012-13 Canadian dollars. This “unconditional access” to Canada’s procurement markets is unparalleled and was seen by European trade negotiators as a significant win.

What does 200,000 SDRs in local food procurement look like? Take, for example,the average family in Canada, which spends $7,980 on food per year, according to Statistics Canada. If an institution procured enough local food to feed 40 families for a year, it would put that spending above the CETA thresholds. While smaller procurement initiatives such as staff cafeterias, vending machines in public spaces, and child care services may have contracts under the 200,000 SDR threshold, local food preferences on larger contracts, which represent the vast majority, will be vulnerable to trade disputes from European and Canadian food suppliers.

Take Sunnyside Home, for example. The live-in care facility, owned by the Region of Waterloo, has a $1-million annual contract with Sysco, a food preparation and marketing multinational, to provide local food for its residents. With CETA in place, Sysco could dispute local food quotas as a prohibited “offset,” described in the agreement as “any condition or undertaking that encourages local development…such as the use of domestic content.”

Many other institutions in the MASH sector have made recent commitments to increase their local food content requirements, which would become similarly vulnerable to challenge under CETA if, over the course of a year, a contract’s value exceeds the SDR threshold. The Harper government frequently claimed food purchases would be exempt, but the CETA text is far from clear on this. The exemption appears to apply only to “human feeding programs,” such as those related to food aid and urgent relief, not day-to-day food contracts.

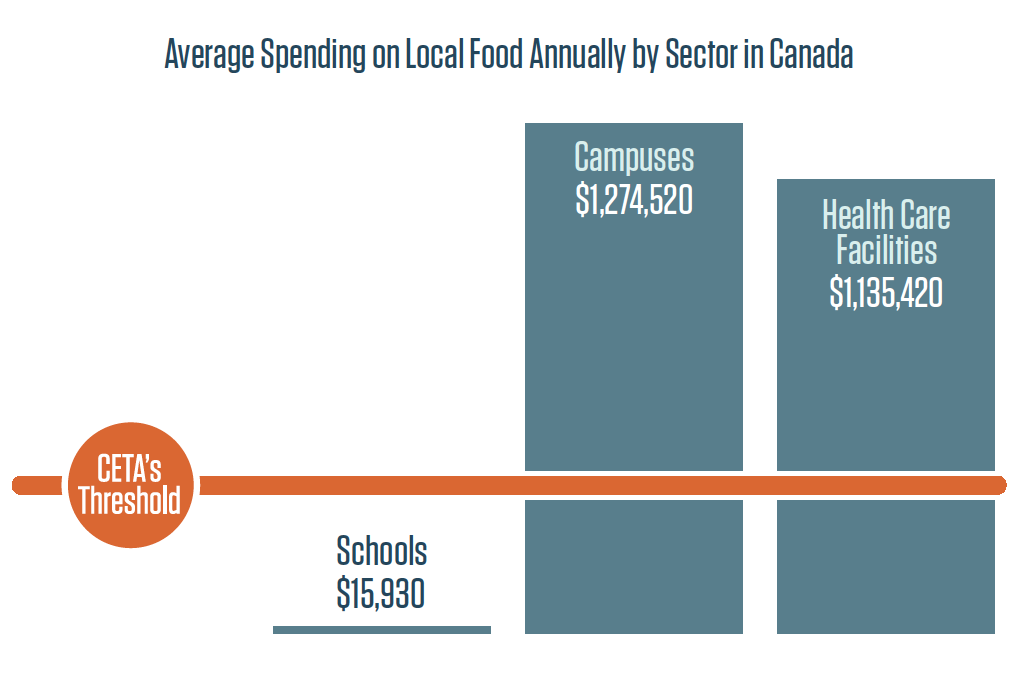

Although there is no national data on the food spending patterns of public institutions, a survey by Farm to Cafeteria Canada represents the most comprehensive attempt to do so. The graph here shows average spending on local food by schools, campuses and health care facilities in Canada through existing Farm to Cafeteria activities. Any funding above the red line would be restricted by the CETA procurement rules.

The impacts will be felt most by hospitals and university and college campuses, which spend a significant portion of their large budgets on local food—3.5 to four times as much as the CETA threshold respectively. Although hospitals currently spend the most on local food, post-secondary institutions are a more promising growth sector for local food procurement.

Before CETA was concluded, over 50 communities had voiced their discontent about the agreement’s procurement provisions. Although the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) was consulted during the negotiations, CETA appears to violate principles the federation said it needed the government to meet before it would support the deal. The provinces and territories had the ability to negotiate their respective procurement commitments, but largely chose to trade away protection of local procurement for limited additional market access for goods and service exports to the EU.

If all goes according to plan, CETA could enter into force next year. However, the ratifying process in Europe may prove complicated. EU member states, including France and Germany, not to mention much of the European Parliament, have cold feet about the investor–state dispute settlement process, which offers multinational investors a means to settle disputes with government outside the regular court system, before a panel of trade lawyers with corporate interests at heart. Public opposition in Europe to investor “rights” in CETA and a similar transatlantic agreement with the U.S. continues to grow.

Even if CETA is ratified, loopholes exist to promote local food through labels that educate consumers about social or environmental criteria (like carbon emission labels) but do not refer to political boundaries. These technical specifications, however, represent relatively weak opportunities for the local food movement to navigate the constraints placed on it by CETA.

The Liberal government claims to have consulted hundreds of people on the TPP since the October election and promises a thorough public debate on whether Canada should ratify the agreement. At the same time, Trade Minister Chrystia Freeland says the government will ratify CETA as soon as possible. Yet, when it comes to public procurement and other areas, the Harper-era EU deal is even more problematic—and lopsided—than the TPP, and clearly in need of its own reassessment.

With respect to local food in Canada, CETA represents a significant barrier to the future of sustainable procurement policies. Municipalities and public sector institutions in the process of scaling up their commitments to local food purchasing will be most affected. CETA contradicts provincial commitments to increase local food provision and threatens the ability of municipalities, provinces and public institutions to prioritize local food, food services and farmers when tendering public contracts.

Amy Wood is a PhD student in political science at the University of Toronto. Her research examines the political economies of trade and climate change, and pathways toward decarbonization.

This article was published in the March/April 2016 issue of The Monitor. Click here for more or to download the whole issue.