Left- and right-wing populist movements that have dominated Prairie politics over the last century can trace their roots back to regional frustrations framed in opposition to heavily urbanized sections of Eastern Canada.

The initial iteration of populism to sweep Prairie politics was a left-wing movement of Western Canadian farmers, trade unionists, and progressives that—spurred on by the Great Depression—gave birth to the early Cooperative Commonwealth Federation. Since the 1980s, Western alienation has become the language of a right-wing populism that blends social conservatism, neoliberalism, and intensified resource extraction.

After a decade or more of waning influence, the Western Canadian style of right-wing populism has surged over the last decade, reshaping federal politics and provincial politics in Western Canadian provinces, to varying degrees.

Under the leadership of Pierre Poilievre, the federal Conservatives have adopted a populist style, making major gains in the last election, despite failing to form government. With an ascendant populist right and the federal Liberal government swinging to a more right-wing stance of business Liberalism, there is a political opening for the Canadian left to articulate a renewed response to right-wing populism that speaks to the present moment of economic uncertainty.

Getting there will require fresh ideas that speak to the class politics of the moment and make clear the deep instability created by Canada’s neoliberal society.

As Simon Enoch and Charles Smith have explained, the form of right-wing populism in vogue among Alberta and Saskatchewan’s conservative politicians can be classified as ‘extractive populism’. While left-wing populisms are constructed around a class-based understanding of economic inequality, the core of extractive populism is a unified regional interest in extractive industries, particularly oil and gas.

In opposition to this unified Western-Canadian interest is an urban ‘elite’, regionally concentrated in Ontario and Quebec, undermining Western Canadians through regulation of extractive industries—according to the right-wing narrative.

Despite evidence to the contrary—Canada has continued, year-after-year, to produce and export record-breaking volumes of oil and gas—the extractive populist framing has more than proven its worth as a political tool.

On the one hand, framing Western Canadians as victims of overly regulatory Eastern elites has allowed politicians to blame the federal government for issues they might otherwise be held accountable for, staving off political rivals. Opportunistically foisting the blame for inflation onto the federal carbon tax provides a case in point, ultimately forcing the abandonment of Canada’s carbon tax.

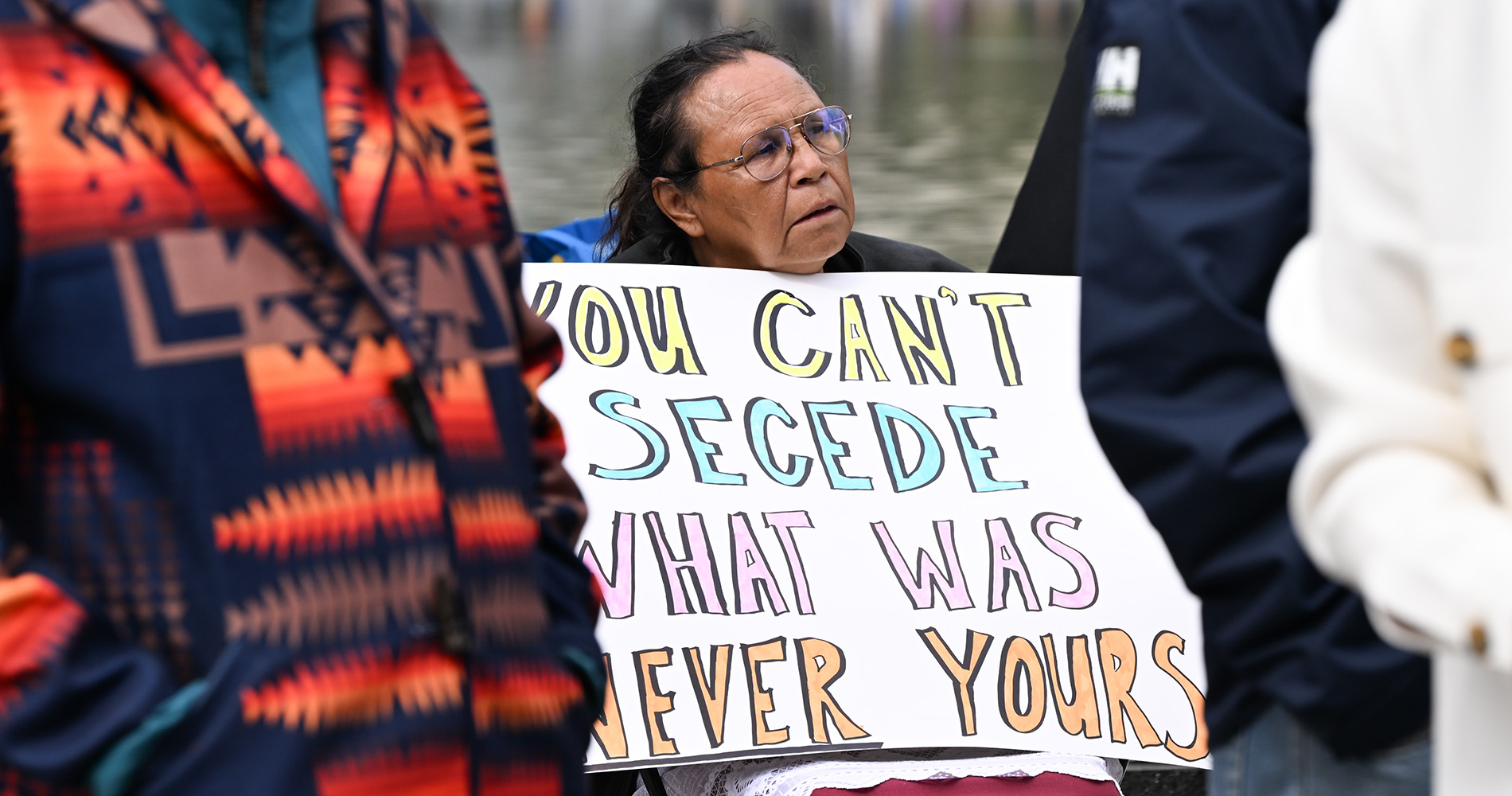

Central to the extractive populist agenda has been utilizing political momentum to further eliminate restraints on corporate power, particularly when it comes to the fossil fuel industry. The Alberta Prosperity Project, one of the main proponents of Alberta separating from Canada, includes in its policy platform plans to cut the corporate tax rate, privatize provincial public services, and eliminate regulations on oil and gas production.

Alberta Premier Danielle Smith has also spoken of the desire to double oil and gas production over the next two decades by eliminating regulation and expanding pipeline capacity.

Pushing back on right-wing populism will require a renewed narrative around issues that working-class Canadians face—affordable food and transportation, housing insecurity, and health care access—and direct frustration towards reining in corporate power and abuse. Like the left-populism that gave birth to the CCF, one that is rooted in class politics.

To start, the Canadian left can look to policy tools to limit market volatility and corporate profiteering during crisis moments, an approach that was used with major success by governments around the world over the last four years.

As Jim Stanford and Erin Weir outlined in a recent report, the primary driver of Canada’s post-lockdown cost of living crisis was a sudden spike in global oil prices following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022. Canada, like other north Atlantic nations, abandoned pricing policies for consumer fossil fuels in the 1980s as part of the neoliberal revolution, leaving gas prices to swing with volatile global markets instead.

In the year leading up to Canada’s June 2022 inflationary peak, higher fossil fuel prices accounted for 43 per cent of cumulative price increases measured by Statistics Canada. This does not account for price increases for other goods and services caused by higher energy costs, which are difficult to track but significant since energy is a key economic input.

This sudden price increase was caused by speculation in global commodity trading markets, which was eye-wateringly profitable for finance and fossil fuel corporations. Profits in the oil futures market tripled between 2019 and 2022. Fossil fuel sector corporate profits were the highest of any sector in Canada during this period: 20 times higher than grocery firms.

Relatively little of this windfall went to fossil fuel workers. Employment and payroll figures remained below pre-pandemic levels throughout this period. Although some of this revenue windfall was captured in taxes and royalties, tens of billions more were paid out in dividends to shareholders and used for stock buybacks.

As Stanford and Weir conclude, there is a direct connection between these mega-profits and the high prices paid by Canadian consumers.

Fossil fuel firms were not only let off the hook for inflation in Canada, frustration over price increases was directed towards the federal carbon tax, an irritant for some sectors of fossil capital. However, in other countries, the response to windfall profits responded directly to the class politics of the moment.

In response to rising energy prices and corporate profits following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Spanish government introduced a cap on electricity prices, a windfall profits tax on large energy companies and a wealth tax.

Following Spain’s lead, windfall profit taxes on large energy firms were adopted across Europe. The funds raised from the windfall profits tax were used to reduce public transit costs in cities across Spain by 30 to 50 per cent, and issue free rail passes for suburban and regional trains. The subsidies increased suburban rail usage by 27 per cent after just a few weeks, delivering savings for commuters and reducing fossil fuel consumption.

This helped Spain’s left-of-centre government stave off a challenge from the radical right.

Inflation can have a pernicious effect on governments. Isabella Weber, one of the leading voices on pricing policy today, wrote in a recent review of populist price regulating strategies, “When people find that through no fault of their own, the goods they can’t live without suddenly become more expensive, they lose trust in the system.”

Pierre Poilievre’s Conservatives clearly grasped this: as inflation ripped through the Canadian economy, he harped on his “Canada is broken” message. But the vulnerability within right-wing populism is that their proposal to fix the system is to turbocharge the free market model that is at the core of the current cost of living crisis.

The Canadian left needs a set of policies to tackle the economic volatility hurting so many Canadians while delivering billions to shareholders. Figuring this out is key for the left to wrestle cost-of-living politics out from the grip of right-wing populists.