An article about Western alienation in British Columbia might as well start with the Rocky Mountains, that formidable natural barrier to the rest of Canada and border to Alberta, our prickly provincial neighbour, and the real hotbed of Western alienation.

The Rocky Mountains themselves are merely the easternmost of a series of mountain ranges eventually reaching the Coast Mountains, which tower over the metropolis of Vancouver, and Vancouver Island, the last mountain range before the vast Pacific Ocean. Those geological barriers have a psychological equivalent, meaning British Columbia often looks more at itself than back to the rest of Canada.

Mountains and forests are the source of the good looks for which B.C. is internationally renowned, as well as the resource wealth that underpins the province’s high standard of living. From the mountains come minerals and timber, from the iconic rivers and coastal fjords come the salmon, and in between, the relative openness of the Okanagan delivers an abundance of fruits and vegetables (and lots of wine these days).

These represent excellent examples of the classic staples economy driven by resource extraction, first described by Harold Innis and expounded by Mel Watkins (perhaps one of Canada’s most important contributions to economics). And while sophisticated service-oriented economies, including tourism, can be readily seen in Vancouver and the bigger cities of B.C., a staples mindset still reigns over most of the province and in Victoria’s halls of power. What’s different is that B.C. has many different resources to sell.

The pull of export markets is in three directions: east to the rest of Canada, south to the United States, and west to Asia. That tilt in orientation has meant a much more diversified pattern of trade. While three-quarters of Canadian exports go south to the United States, for B.C., it’s just 53 per cent (in 2024) with 37 per cent of B.C. exports going to Asia.

Even after crossing the Rockies, the distance “back east” to the centre of Canada is astonishingly massive, and three time zones away. A lot of public discourse this year has concerned supposedly large interprovincial trade barriers that are holding back east-west commerce. This is mostly nonsense and political theatre. The real barrier is long distances and transportation cost: from Vancouver to Calgary is a nine-hour drive, and it’s about 4,400 km to the major centres of Toronto, Ottawa or Montreal.

And yet, Canada’s far West, ironically, lacks a Western alienation vibe. Perhaps because it’s as far west as you can go, and once here most people don’t want to go back—that is, if they can afford to stay amid Canada’s highest cost housing. Perhaps it’s because B.C. joined Canada in its early days, and the feds built a railroad to connect Toronto and Montreal to B.C. well before Alberta and Saskatchewan were carved out as provinces.

B.C. wears Canada with a casual grace other provinces can’t dream of: there’s the Vancouver Canadians baseball club (a farm team of the Toronto Blue Jays) and Vancouver Canucks hockey club; it was the Trail Smoke Eaters that brought to Canada a world championship in hockey back in 1939.

I suspect that Alberta’s Western alienation stems from its singular focus on oil exports, whereas B.C. is much more diversified. Periodic changes in commodity prices, world events or federal policy can drive larger economic swings in Alberta. The province’s reliance on fossil fuels portends a clash when the federal government attempts to implement a National Energy Policy (as the first Prime Minister Trudeau did in the early 1980s) or to address the global collective action problem of climate change (as the second Prime Minister Trudeau did over the past decade).

When it comes to oil and gas, however, B.C. has more in common with Alberta than cosmopolitan Vancouver cares to admit. B.C.’s Northeast corner, which deviates from the Rockies into a chunk of foothills and prairie that is geologically connected to Alberta, also known as the Western Sedimentary Basin, with vast reserves of fossil fuels. B.C.’s production is more geared to gas than oil but the political grip on the provincial legislature has similar fingerprints.

B.C. only consumes a small portion of the gas that is extracted and much of it goes south to the U.S. and east to Alberta. The Trump tariff war has advanced interest in getting gas from B.C. to tidewater for export as liquified natural gas (LNG). Canada‘s first LNG export terminal opened in Kitimat, B.C., in July 2025, essentially a giant refrigerator to transform gas into liquid form for loading onto tankers to ship anywhere in the world.

B.C.’s unique spirit comes alive around nature and environmental issues. The international organization Greenpeace was started in B.C. by a group of concerned hippies (outside Vancouver, other hippie and U.S. draft dodger outposts include Nelson and Smithers). In the 1990s, the “war in the woods” over clearcut forestry was centre stage, while today it’s more about climate change caused by fossil fuels. B.C. was an early leader on climate action, with Canada’s first carbon tax in 2008 anchoring a Climate Action Plan. Alas, these efforts to decarbonize the B.C. economy have been undermined by a B.C. government that has actively encouraged more oil and gas production.

British Columbia is perhaps the most colonial in the history of place names, and there remains a lot of British in the institutions and the core structures of society. B.C.’s oldest and racist tendencies have largely given way to the diversity of immigrant populations from around the world. As much as B.C.’s gaze has strayed over the Pacific Ocean, Asia has long been gazing back—witness the large number of Chinese, Japanese and South Asian settlers over the decades.

Yet, it is Indigenous cultures that give B.C. its deepest sense of meaning, reflecting thousands of years of continuous settlement manifested in distinctive carvings, totem poles, and languages. Leaving the orbit of Metro Vancouver and the South Coast, it does not take long before one is absorbed in the wilderness, where the pull of Indigenous cultures is strong.

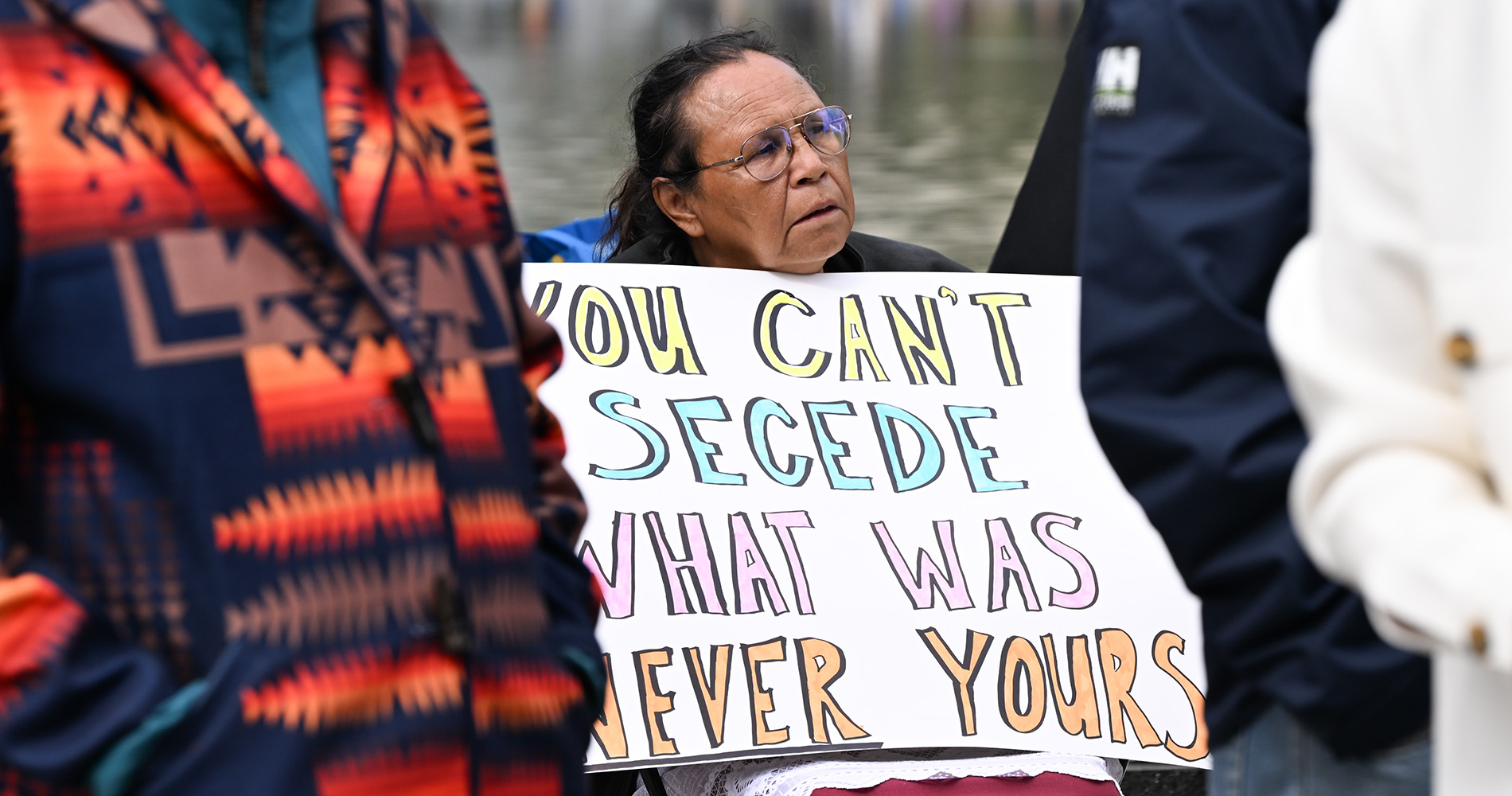

B.C. has set on a pathway to reconcile with dozens of First Nations who never signed the treaties that define much of Canada’s relationships with Indigenous Peoples. And as First Nations recover from decades of brutal colonization, they are increasingly flexing their muscles, generating income from new economic development to energy production and real estate development.

B.C. is Emily Carr to the rest of Canada’s Group of Seven. Common threads but, ultimately, a unique proposition. B.C. does its own thing, and with a federal government that is so far away, much of the political attention is on the provincial government. And while B.C. might suffer from narcissistic impulses, there’s no talk of separation. People love being part of the dysfunctional family called Canada, even if sometimes we lock ourselves in our room and complain that nobody understands us.