The following is a re-print of the August 2025 edition of Shift Storm, the CCPA’s monthly newsletter which focuses on the intersection of work and climate change. Click here to subscribe to Shift Storm and get the latest updates straight to your inbox as soon as they come out.

Limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels was always an “aspirational” target. Achieving it was never particularly likely, but at the time it was negotiated—as part of the 2015 Paris Agreement—it was at least plausible.

More importantly, it provided a science-backed rationale for aggressively scaling up climate action. Do everything we can as quickly as we can and it is possible for the world to avoid the worst consequences of climate change.

The window for achieving 1.5 degrees has now closed. The planet actually hit the 1.5 degree mark in 2024 for the first time. And while last year’s heat was exacerbated by El Niño, we are unavoidably on track in the next few years to lock in 1.5 degrees of warming as the new, permanent baseline.

Average surface temperatures are not the only metric we need to be concerned about, of course, as the latest Indicators of Global Climate Change report makes clear. Global sea levels, for example, rose by nearly half a centimetre in 2024 and are now 22.8 cm higher than they were in 1901.

Incidentally, Canada is in the midst of our second worst wildfire season ever, surpassing 2024 and trailing only 2023 in terms of hectares burned—a worrying trend unequivocally driven by climate change. Homes are being destroyed from coast to coast, and fire season is expected to continue well into the fall.

But every measure of climate change is fundamentally driven by rising temperatures and, consequently, limiting global warming remains the most important policy imperative of the 21st century—no matter how far it has fallen down governments’ priority lists.

The Paris Agreement’s official two degree target remains within reach if we can achieve net-zero global emissions by mid-century. That is and will remain the primary focus of most climate advocacy.

But spare a thought for 1.5 degrees—a target that represented global climate action at its most hopeful. We will need plenty more of that hope moving forward.

* * *

It’s a short newsletter this month as many publishers slow down for the summer. Before we turn to the research, I wanted to quickly acknowledge the teachers and professors currently gearing up for another year of educating on climate change, environmental policy and related issues. It’s more important than ever that students are equipped to engage with the science and politics of climate. If you are still preparing your course outlines and looking for guest lecturers, get in touch!

Storm surge: this month’s key reads

Pragmatic responses to unprecedented economic warfare

Canada’s largest private sector union, Unifor, has released a series of statements that address the impacts of Trump’s trade war on Canadian workers in 15 different industrial sectors. Together, the statements paint a vivid picture of the damage American economic policy is wreaking, but they also offer a vigorous repudiation of appeasement in any form. Instead, the union is calling for aggressive retaliation from the federal government paired with targeted support for domestic workers and industry.

Of particular interest to this newsletter are the statements on autos, mining and rail. Each sector faces unique challenges, but all present an opportunity to pivot away from American dependence. Stronger domestic supply chains complemented by international market diversification are the foundations, none of which will happen in the absence of a concerted industrial strategy.

These themes are taken up in an important new factbook, Building a Sovereign, Value-Added, and Sustainable Economy, written by economist Jim Stanford and published by the CCPA. The report provides an overview of 15 different dimensions of the Canadian economy as context for a forthcoming meeting of progressive economists, but the lessons are useful for all of us.

Among the central economic challenges facing Canada are dependence on the U.S. market and the export of unprocessed, low-value resources. They are hardly novel concerns, but the Trump-induced crisis has laid bare these structural weaknesses. Solving them will require “more investment, innovation, trade, work, and care – across the full scope of the economy,” an approach that, again, is only possible with state-led industrial strategy rather than naive deference to market leadership.

One consideration Stanford highlights that is unfortunately downplayed in Unifor’s positions is the importance of tackling greenhouse gas emissions and scaling up renewable energy. Decarbonizing the economy is not only an environmental priority. It also allows us to decouple from the U.S.-dominated fossil fuel trade and to reduce domestic energy costs—a win-win opportunity.

Research radar: the latest developments in work and climate

Laid-off fossil fuel workers do not bounce back to their previous earnings… and that might be OK. A study by the OECD and Statistics Canada concludes that workers displaced from high-emission industries, such as oil and gas, are earning 29 per cent less, on average, six years later. Worries about lower incomes are one of the biggest sticking points for many oil and gas workers (and their unions) that are otherwise open to transitioning to cleaner industries. What’s missing from the discourse is the heights that these workers are falling from—average total compensation in oil and gas is over $200,000, a remarkable anomaly in the Canadian workforce—which means most are landing well-paid jobs anyway. We need to refocus the conversation not on incomes, a measure on which no other sector can reasonably compete, but on other measures of decent work and quality of life, which all workers are entitled to.

“Elbows down” approach to Trump will cost Canada in the long run. Speaking of appeasement, my colleagues Marc Lee and Stuart Trew have written a useful and sobering overview of the U.S. tariff war from a national and global perspective. They document a cascade of corporate-driven capitulation to U.S. political pressure, in Canada and elsewhere, that is ultimately self-defeating. Making preemptive concessions to an unreliable partner only hurts Canadian workers and industry with no guarantee of better treatment.

Is military spending a climate opportunity? An article by Hema Nadarajah in Policy Options, “Greening the military,” explores how Canada’s enormous new defence budget can be used to address climate change—or at least to avoid making it worse. Defence already accounts for more than half of federal government emissions in Canada, so it’s a question worth asking even if you disagree with the scale of new spending.

Community climate action essential for national progress. A report commissioned by a group of U.S. ENGOs, Changing the Game, finds that community-level climate strategies not only reduce emissions but also create more durable support for climate action than national-level actions alone. It’s a helpful reminder of the importance of pairing bottom-up organizing with top-down policy support, something my co-authors and I called for in Don’t Wait for the State.

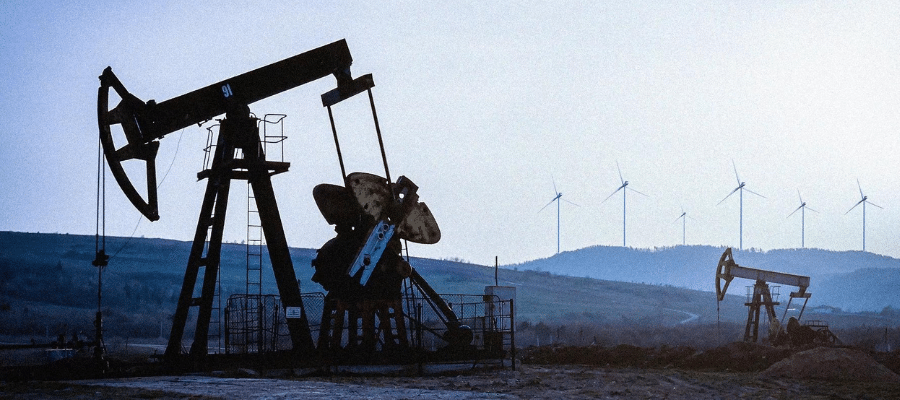

LNG investment is a barrier to scaling renewables. An article published in the journal Cell Reports Sustainability, “Locked in a fossil-centric system paradigm,” challenges the notion that liquefied natural gas (LNG) infrastructure can be productively developed in Europe while simultaneously scaling up renewable energy alternatives. This “all-of-the-above” approach may be popular with governments and the corporate sector, but in practice it locks in fossil dependence while siphoning investment and policy support away from a genuine energy transition.

New renewables are increasingly cheaper than new fossil fuel power. It’s been true for several years now, but the cost gap between renewables and fossil fuels continues to widen. As the International Renewable Energy Agency’s latest Renewable Power Generation Costs report concludes, more than 90 per cent of recently built, utility-scale renewables are delivering power cheaper than even the cheapest fossil fuel alternative. There is absolutely no reason to be considering new coal and gas-fired power plants when cleaner and more cost-effective options are on the table.

Community solar is a social and environmental boon for South Africa. The investigative journalism outfit Oxpeckers has published a wonderfully titled long-form article, “People who own the sun,” about socially-owned renewable projects in South Africa. It’s a case study in the potential for under-developed communities to leapfrog corporate-controlled fossil fuel infrastructure directly to distributed clean energy projects. Like Indigenous-led projects in Canada, these are win-win opportunities for people and the climate.

Oil and gas industry pollution disproportionately harms racialized communities. Yet another study, this one in the journal Science Advances, finds that racialized communities experience a disproportionate health burden from oil and gas-related pollution. The worst harms are connected to oil and gas processing, such as refineries, which are often located in populated areas. The paper is useful because it focuses on oil and gas pollution specifically, whereas most previous research lumps O&G in with coal.

Climate change is driving rising food prices. Extreme weather is the most obvious impact of climate change, but the most consequential in the long term may be its effects on agriculture. An article published in the journal Environmental Research Letters, “Climate extremes, food price spikes, and their wider societal risks,” highlights several examples from recent years of specific commodities increasing in price by as much as 300 per cent due to extreme heat and droughts. At this rate, food prices could become the central political consideration for climate action in the years to come.