First Nations in Alberta have strongly voiced opposition to Bill 54, also known as the Election Statutes Amendment Act. The bill has been widely interpreted as opening the door for a referendum on Alberta separating from Canada, a move the First Nation leaders say disregards Canada’s relationship with Indigenous signatories to the numbered Treaties.

In the case of Alberta, the First Nation signatories to Treaties 6, 7 and 8 have reserve lands within the province and the territory of Treaties 4 and 10 also overlap Alberta.

The disregard of the treaty relationship has also been expressed as being against treaty rights. The effort to protect treaty rights has often focused on whether a referendum is legal to begin with. The legality of a referendum has been attacked on multiple fronts.

First, would the constitution of Canada allow for such a break? Here, First Nation leaders point out that the Canadian constitution is founded on the historic relationship between First Nations and the British crown. It is not possible to dissolve the treaty relationship unilaterally because Indigenous collectives have independent sources of political authority that are not dependent on the goodwill of Alberta or Canada.

From an Indigenous legal perspective, Leroy Little Bear has argued that within a plains Indigenous tradition, land was communally held, not just within a community but with other living beings as well. When Indigenous Peoples signed treaties, land was not held exclusively by humans, so First Nation people could only negotiate the ability of humans to share the land with each other.

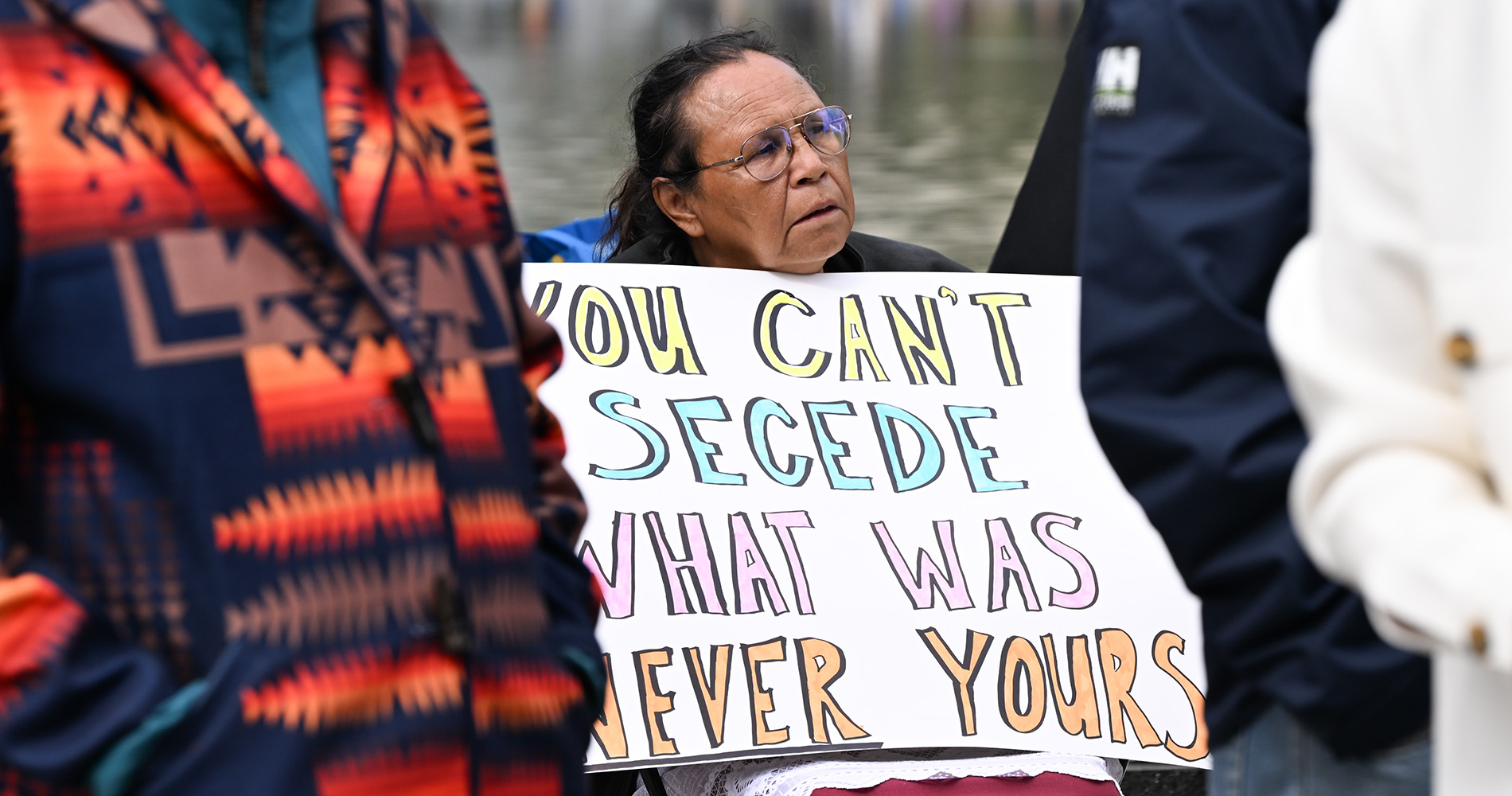

From this standpoint, the only rights in land Alberta holds is to share the land with Indigenous Peoples. It does not have the right to legally separate. From the perspective articulated in the press releases from well over a dozen First Nation governments and organizations, the results of a referendum are inconsequential because such an action is unlawful.

The legal position of First Nations has been championed by Albertans and other Canadians who are deeply troubled by the passing of Bill 54. Take prominent entrepreneur Arlene Dickinson, who had this to say on her substack: “I’ve been genuinely stunned by what Premier Smith is saying and doing. … She’s asserting control over land that doesn’t belong to her. That land is subject to Treaty rights which are legal agreements between the Crown and Indigenous Nations that are protected under the Constitution. These rights aren’t optional. They aren’t symbolic. They’re binding.”

While I wholeheartedly agree Alberta separation disregards Treaty rights and is illegal, I also think it’s missing what is most dangerous about this situation for Indigenous Peoples. The danger is not Alberta separating, the danger is the Alberta separatist movement.

Kathleen Martens at APTN has looked at how Alberta’s separatist movement would treat Indigenous Peoples. The Alberta republican party envisions abandoning existing treaties and starting over. Such a policy position would rewind the clock over 50 years and is reminiscent of the 1969 White Paper from the federal government that sought to end political relationships that recognized the distinctive legal and political rights of First Nations.

From Indigenous legal traditions, Alberta separating is certainly illegal, but focusing on the legality of Alberta’s separation distracts from the danger posed by an emboldened Alberta separatist movement.

I first started thinking about the long-term consequences of the Alberta separatist movement after learning more about the history of the Brexit referendum. Held in 2016, the popular vote to leave the European Union stunned mainstream commentators.

British Prime Minister David Cameron felt the Brexit referendum was needed to hold together different factions of the Conservative Party. Cameron felt a referendum would allow Eurosceptics within the Conservatives Party to have their grievances acknowledged and be an outlet to voice their frustrations. Yet Cameron himself campaigned to stay within the European Union and was aligned with the moderate wing of the Conservative Party.

Cameron’s strategic error: he thought there was no possible way the “Leave” campaign would triumph. It resulted in Cameron’s resignation as prime minister and the departure of Britain from the European Union.

There are some parallels to the United Conservative Party of Alberta (UCP) and Danielle Smith. First, the UCP has clear factions. In the spring of 2022, Jason Kenney resigned as leader of the UCP, not long after allegedly saying in a closed-door meeting: “the lunatics are trying to take over the asylum”, in response to the most conservative faction of the party, which felt public health measures were government overreach.

During the leadership campaign to replace Kenney, four candidates held a press conference to voice their opposition to Danielle Smith’s campaign platform to pass an Alberta Sovereignty Act.

The UCP used a voting method known as instant run-off voting. Party members could rank one to six of seven candidates. Each round, one candidate was dropped and their votes went to whomever was the next ranked candidate on each ballot.

Danielle Smith led from start to finish but required the maximum six rounds of voting to achieve a majority. Of 84,193 voters who cast a ballot, only 42,423 ranked Smith as a desired candidate.

Like Cameron, Smith says she is against separation and supports “a sovereign Alberta within a united Canada”. It is not a huge leap to reason that Smith is using the same strategy as Cameron—the hope that a referendum will satisfy the ambitions of the far right of the UCP while keeping everyone under the same party tent.

While I cannot predict the future, I think it’s reasonable to assume a referendum will likely embolden a separatist movement within Alberta by giving separation a platform and resources, allowing the separatist movement an opportunity to test what messages have purchase with people beyond their base.

Any growth of the movement will likely provide motivation to continue—even if the vote goes against them. Emboldening a separatist movement will change the political landscape for First Nation people by solidifying a base that views negotiating with First Nations as a last step, not a first step. The Alberta separatist movement’s position towards First Nations is more reminiscent of the policy of assimilation expressed in the 1969 White Paper than any other organized political movement in Canada.

While the UCP introduced amendments to declare that any separation referendum cannot undermine existing treaty rights, First Nation people should have no faith in legal protections shoehorned in at the last minute. After all, the borders of Alberta and Canada were both drawn with no regard to Indigenous Peoples’ own legal orders.

We should assume colonial governments will create a legal reality for themselves that allow them to accomplish whatever ambitions they have in mind. Rather than focus solely on the law, First Nation people must have a political analysis of what an emboldened separatist movement will mean.

The danger of this movement goes beyond the possibility of separation. The danger of the separatist movement is strengthening clear-cut sources of hostility against Indigenous Peoples in Alberta.