A couple of years ago I went to see my aunt at a seniors’ home in rural Saskatchewan. An elderly gentleman passed by and I was introduced as visiting from Ottawa.

“Oh,” he said, puffing up. “Did you bring Trudeau with you?”

He proceeded to rant, not only about then Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, but his father before him. If you’ve ever spent time in rural Alberta and Saskatchewan, you might have come across this certain disdain for Ottawa.

I grew up with it, not fully understanding why Ottawa was pronounced like it was a swear word.

Eventually, I came to learn about the deep sense of grievance that fuels Western alienation on the Prairies. As Ricardo Acuna writes in this issue of the Monitor, Western separatism is an age-old story—one that’s entering a new chapter.

Just as most Canadians are feeling an extraordinary wave of nationalistic pride in the face of Trump’s odious politics, a new wave of Alberta separatism—fuelled by the politics of oil and gas—has spilled onto the scene.

Rather than uniting to fight Trump and assert Canadian independence, a group of right-wing populists are seeking independence from Canada. Alberta Premier Danielle Smith is playing right into their hands, promising a referendum on the subject next year. Meanwhile in Saskatchewan, Premier Scott Moe uses every opportunity to blame Ottawa—often for problems that are within his own power to fix.

As Simon Enoch writes in this issue, “To listen to politicians like Alberta’s and Saskatchewan’s premiers, the recent rise in Western separatist sentiment has nothing to do with them, it is rather an inescapable by-product of Ottawa’s longstanding neglect of the west and its (energy) interests.

“But such Western Canadian politicians have not been mere spectators sitting idly by with mouths agape as the flames of western discontent have gathered strength,” Enoch writes, “No, they are the arsonists.”

Canada’s federation has never been perfect. It was, after all, built on the foundations of colonialism—at the expense of exploited migrant labour and the violation of Indigenous Peoples’ rights, livelihood, and lives.

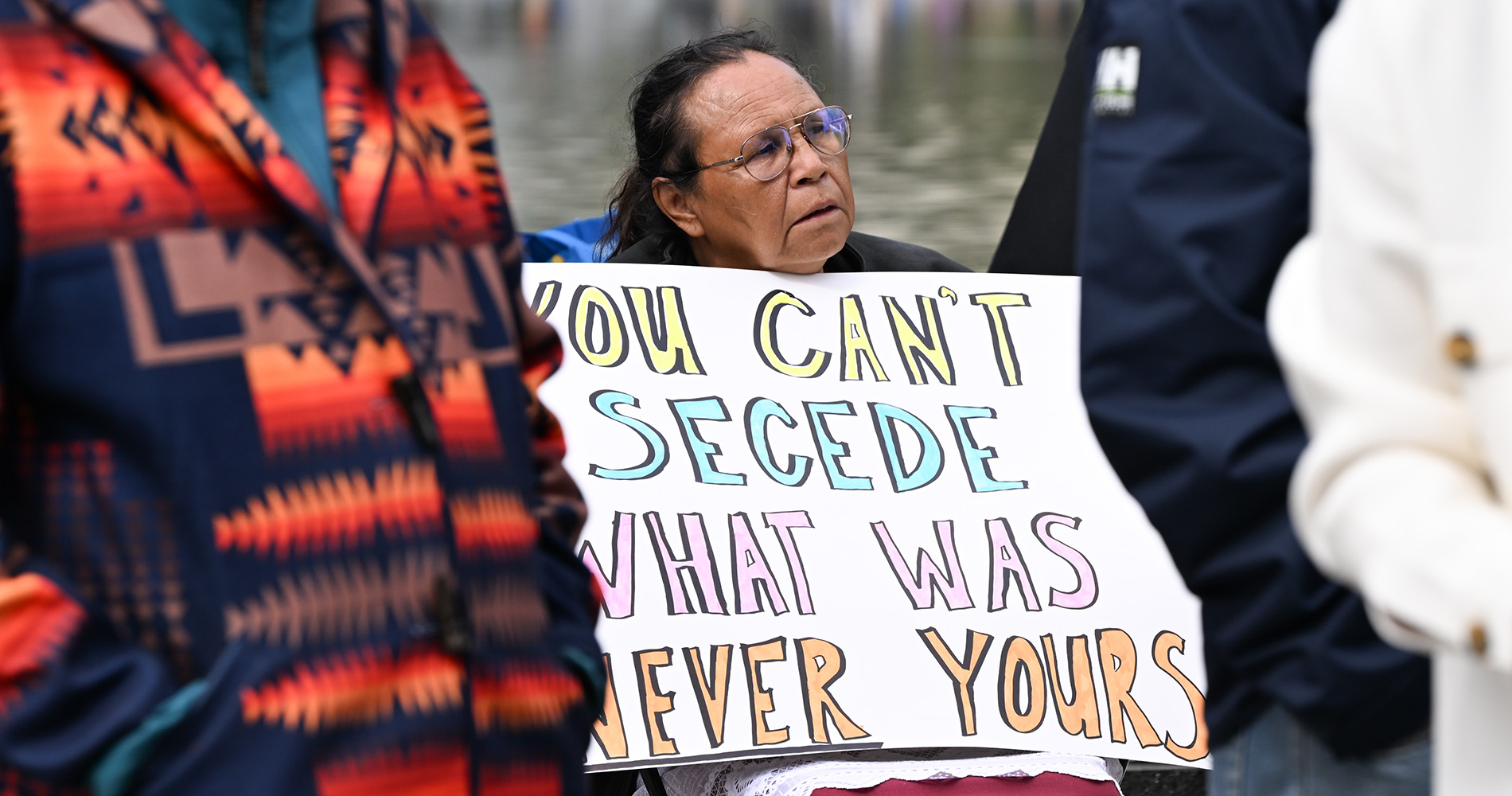

Indeed, any serious move towards Alberta separatism would face serious challenges from First Nations themselves. As Matt Wildcat writes in this issue, “First Nations in Alberta have strongly voiced opposition to Bill 54, also known as the Election Statutes Amendment Act. The bill has been widely interpreted as opening the door for a referendum on Alberta separating from Canada, a move the First Nation leaders say disregards Canada’s relationship with Indigenous signatories to the numbered Treaties.”

Treaty rights are not just symbolic, Wildcat writes, they’re binding. But Wildcat also comes with a warning:

“While I wholeheartedly agree Alberta separation disregards Treaty rights and is illegal, I also think it’s missing what is most dangerous about this situation for Indigenous Peoples. The danger is not Alberta separating, the danger is the Alberta separatist movement.”

Should Alberta’s separatist movement succeed, it would no longer have Ottawa to kick around. In fact, Alberta would face new headaches—of its own making.

Its reliance on oil, in a world that will inevitably turn away from that market as the climate crisis worsens, would leave that province with few economic cards to play. And, as Wildcat warns, the success of a separatist movement would give rise to ugly social and political dynamics. For a glimpse, see what’s happening to the south of us.

As Stewart Prest writes, “[T]he long and short of it is that a sovereign Alberta would be condemned to be free, but not free of obligations. In the place of constitutionally guaranteed enforceable rights, its residents would have only what its government can negotiate with its sovereign neighbours.

“Alberta and its government would be on its own, for better—and for worse.”

That elderly gentleman at my aunt’s seniors’ home might be cheering on the separatists, hoping it takes root in Saskatchewan. But a wise person once told me: be careful what you wish for.